by Roger Green

(click on images to enlarge)

Simon Theobald, Bishop of London, Archbishop of Canterbury, Chancellor of England, beheaded in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, occupies a singular position within the public consciousness of Sudbury. Some Sudburians recognise the name, some others can point out the connection with the Talbot on the coat of arms of the town. Beyond that there seems to be more doubt about whether Simon should be regarded as hero or villain. In the recesses of my mind I knew that Simon had been in the service of the Pope and, unthinkingly, had always assumed that this had taken place in Rome. Indeed quite a few articles on Simon happily support my errant view. If such were to be the case then this article would need to explore an ‘Italian Job’ rather than a ‘French Connection’.

For about 70 years of the 14th century, the papacy was not based in Rome. The Pope took up residence in Avignon, on the banks of the Rhone in the south of France, in 1309 and a procession of Popes, following that date, set about building and extending their papal palace there. It is one of the most impressive buildings that I know. It has a strongly medieval grandeur. It was there, in Avignon, that Simon worked for two resplendent and entirely different Popes.

Simon was born nearly 700 ago. Most sources accept that he was born in Sudbury but that is probably not the truth. Recent investigation suggests East Dereham in Norfolk as his birthplace. He was the son of a fairly well-to-do merchant and clothier by the name of Thebaud or Thibaud. From the outset, I must plead a French connection because Thibaud is a fairly common French surname, anglicized to Theobald. In 1290 an early mention of the Theobald family in Sudbury records William Theobald as operating a Fulling Mill which he either owned or leased from the Manor. Simon’s father, Nigel, was born circa 1295 and, at the age of 20 years, married Sarah. They lived and raised four sons in a substantial house to the west of St. Gregory’s church. It is recorded that, during the years 1330 – 1345, Nigel Theobald was buying and selling huge quantities of wool and cloth. He had become one of the new mercantile class to whom Edward III looked in order to finance his campaigns in France. According to the Close Calendar Rolls 1330 – 1345 Nigel was loaning the king sums equivalent to £15.000 and £20,000 today. In 1343 Nigel was providing furs and cloth to Elizabeth de Burgh, of Clare Castle, the grand-daughter of Edward II. She was in possession of the Manor of Sudbury and through her the town expanded with the creation of Market Hill, North Street and Borehamgate. Nigel was often included in her lavish entourage at Clare Castle. All these connections would doubtless have assisted the careers of his sons. Nigel traded goods from all over Europe, dyes and furs in particular, exporting cloth and finished products in return.

Simon went up to the University and probably read Law at Cambridge. Certainly he later made gifts to the University. Persuing his French connection again, he probably continued his studies in Paris, incepting as a Doctor of Law. Cambridge, 700 years ago, would have been unrecognisable. Even the iconic landmark of King’s College Chapel would not be built for another 100 years. Only Peterhouse and Clare colleges existed. The former had been established for about 50 years and the latter for only 10 years. Simon, like most of his contemporaries, would probably have been fairly fluent in both Latin and French.

In 1344 Simon was presented to his first benefice at Wickhambrook near Newmarket and shortly afterwards received another benefice, some miles north, at Herringswell. The latter was in the gift of the Abbott of Bury St Edmunds. It would be interesting to discover what proportion of time Simon spent in either parish. Was he ever in either? By a strange and macabre coincidence for a man who was later beheaded, Herringswell church was somewhat unusually dedicated to Saint Ethelbert, a saint beheaded in the 8th century.

Already subject to the Abbot of Bury St Edmunds through Herringswell, by 1345 Simon had entered some kind of further service to the Bishop of Norwich, William Bateman.

The stage was set for Simon to become embroiled in a bitter dispute between the Bishop and the Abbott. In the course of the dispute, Simon was one of a group who published an excommunication order on one of the Abbott’s attorneys and that action led to a Royal Order for Simon’s arrest and imprisonment. So it was that, to avoid arrest, that Simon fled the country, probably in the summer of 1346 and settled in Avignon where he stayed for at least 10 years – roughly a quarter of his adult life.

We might investigate what it was that made Avignon attractive as a destination. Paris might have been a more obvious choice but, given that England and France were at war and that the French, in 1346, suffered a cataclysmic defeat at the battle of Crecy, the possible neutral protection of the independent Papal territories around Avignon might well have appeared to be more attractive than the seat of the King in Paris. The Avignon court of Pope Clement VI had a flamboyant and lavish reputation throughout Europe and it is perhaps not easy to recognise this reputation as an attraction to a man who was described as ‘learned, eloquent and liberal’. In Avignon, Simon certainly continued to press Bateman’s case to the Pope. Perhaps that was his reason for being there. Much later in his career, Simon donated funds to Trinity Hall, Cambridge which Bateman founded in 1350.

Four years before Simon’s arrival, Clement VI had set about doubling the size of the Papal Palace. Simon would have witnessed the construction.

I doubt that Simon remained uninspired by Clement’s mighty construction. Years later, as Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon set about rebuilding the nave of Canterbury Cathedral.

Upon becoming Pope, Clement VI had famously proclaimed, ‘My predecessors did not know how to be Pope!’ To prove it he held a banquet with 3,000 guests, an indication of the avalanche of extravagance and splendour that was to descend on Avignon until the papal city outshone all the royal courts of Europe. Prepared for the feast were 1,023 sheep, 118 cattle, 101 calves, 914 kids, 60 pigs, 10,471 hens, 1,440 geese, 300 pike, 46,856 cheeses and 50,000 tarts. As Clement said, ‘A pontiff should make his subjects happy.’ Small wonder that Clement was known as ‘Clement the Magnificent’ and he made sure that he ‘lived’ the title to the full in sumptuous luxury and profligate self-indulgence, with a vast army of attendants, unquestioned authority, and morals suited to his purpose. Clement’s Papal Court in Avignon cost ten times that of the French Royal Court in Paris. All Sundays and Holy Days were marked with flamboyant processions through the town. Clement was also highly intelligent, with doctorates in law and theology. He had been an abbott, an archbishop and, in a strange pre-echo of Simon’s own future career, Clement had been Chancellor and Chief Minister of France. He was an impressive public speaker. His sermons were renowned.

We read that ‘scores of hopeful clerics…returned in droves seeking lucrative benefices…. which he graciously handed out. It is impossible to overlook Clement VI’s huge generosity. He gave away 100,000 benefices during his papacy. Simon was made a Canon of Lincoln, a Canon of Hereford, a Canon (some say Chancellor) of Salisbury and some also say a Prebendary (Canon) of Henstridge near Wells. Simon would have found it inconveniently troublesome to appear in any of these places as, in England, he was still an outlaw with a warrant for his arrest. Edmund Mullins writes that ‘Avignon was a haven for careerist churchmen, delighted to be able to draw a comfortable income from parishes they rarely visited, while they themselves enjoyed the fleshpots of the Papal court.’ It would be illuminating to understand how much of that description was applicable to Simon. Perhaps we should also remind ourselves that the Avignon Popes owned all the best Cote de Rhone vineyards and indeed they founded Chateauneuf du Pape.

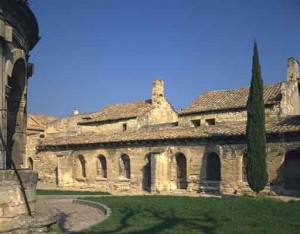

The ruins of the Pope’s castle at Chateauneuf du Pape

The ruins of the Pope’s castle at Chateauneuf du Pape